Why Americans Smile So Much

How immigration and cultural values affect what people do with their faces

On Reddit forums that ask “What’s a dead giveaway that someone is American?” one trait comes up over and over again: big, toothy grins.

Here’s how one Reddit user in Finland put it:

When a stranger on the street smiles at you:

a. you assume he is drunk

b. he is insane

c. he’s an American

Last year, I wrote about why some countries seem to smile less than average—and mistrust those who do seem unusually peppy. A country’s level of instability, that study found, might be why people who seem happy for no reason in, say, Russia, are considered foolish.

But there’s an interesting line of research that helps explain outliers on the other end of the spectrum, too: Americans and their stereotypically mega-watt smiles.

It turns out that countries with lots of immigration have historically relied more on nonverbal communication. Thus, people there might smile more.

For a study published in 2015, an international group of researchers looked at the number of “source countries” that have fed into various nations since the year 1500. Places like Canada and the United States are very diverse, with 63 and 83 source countries, respectively, while countries like China and Zimbabwe are fairly homogenous, with just a few nationalities represented in their populations.

After polling people from 32 countries to learn how much they felt various feelings should be expressed openly, the authors found that emotional expressiveness was correlated with diversity. In other words, when there are a lot of immigrants around, you might have to smile more to build trust and cooperation, since you don’t all speak the same language.

People in the more diverse countries also smiled for a different reason than the people in the more homogeneous nations. In the countries with more immigrants, people smiled in order to bond socially. Compared to the less-diverse nations, they were more likely to say smiles were a sign someone “wants to be a close friend of yours.” But in the countries that are more uniform, people were more likely to smile to show they were superior to one another. That might be, the authors speculate, because countries without significant influxes of outsiders tend to be more hierarchical, and nonverbal communication helps maintain these delicate power structures.

So Americans smile a lot because our Swedish forefathers wanted to befriend their Italian neighbors, but they couldn’t figure out how to pronounce buongiorno. Seems plausible. But there’s also something very w i d e about the classic American grin. Why is it that Americans smile with such fervor?

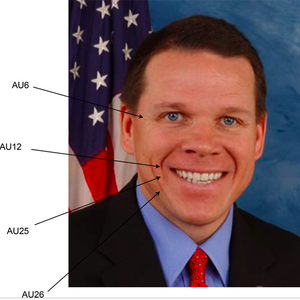

This could be because Americans value high-energy, happy feelings more than some other countries. For a study published last year, researchers compared the official photos of American and Chinese business and government leaders. After coding them according to their levels of “facial muscle movement,” they found that American leaders in all contexts were both more likely to smile and showed more “excited” smiles than the Chinese leaders did.

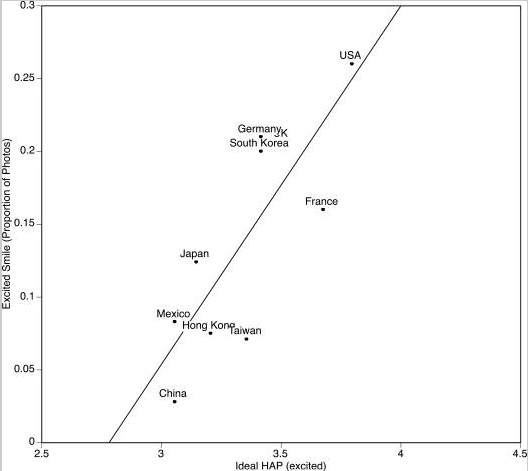

Later, they asked college students from 10 different countries how often they would ideally like to experience certain emotions—from happiness to calmness to hostility—in a given week.

Then, they looked at photos of legislators from those 10 countries. They found that the more a country’s college students valued happy, high-energy emotions, like excitement and enthusiasm, the more excited-looking the government officials looked in their photos. (The correlation held after controlling for economic indicators like GDP.) Interestingly, the amount that people in those countries actually felt happy didn’t matter. The leaders’ excitement appeared to reflect the ideal emotional states of their constituents, not their actual ones.

Other than causing consternation for tourists, these cultural differences in the value and uses of smiles are also why it can be hard for iconic American companies to expand overseas. As a recent episode of Invisibilia showed, when McDonald’s entered Russia in the ’90s, they had to coach their employees on how to smile. Here’s how Yuri Chekalin, a former McDonald’s employee, described the experience to Invisibilia host Alix Spiegel:

CHEKALIN: It was an American video, and it was just dubbed in Russian. How you’re supposed to smile, how you're supposed to greet.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: Glad you came in, hope to see you again real soon.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: You bet.

SPIEGEL: And then the lights came back on, and the trainers got down to work breaking down the elements of American cheerfulness into digestible component parts. For example, when you meet someone, you must make direct eye contact, which seemed deeply strange to Yuri.

CHEKALIN: So in Russia we used to—if somebody looks at us, we just kind of look the other way, unless we about to fight or something like that. But in America, he says, you know, when you making eye contact, you smile.

And when Wal-Mart opened stores in Germany, the company also had to tweak its chipper ways to better suit the sober local mores, as The New York Times reported in 2006:

Wal-Mart stopped requiring sales clerks to smile at customers—a practice that some male shoppers interpreted as flirting—and scrapped the morning Wal-Mart chant by staff members.

“People found these things strange; Germans just don’t behave that way,” said Hans-Martin Poschmann, the secretary of the Verdi union, which represents 5,000 Wal-Mart employees here.

It wasn’t enough, alas: Wal-Mart pulled out of Germany that year after losing hundreds of millions of dollars. There were other cultural differences at play, like Wal-Mart’s failed attempts to get its German employees to relocate. And while the bosses back at Wal-Mart’s Bentonville, Arkansas, headquarters might have been cheerier than their Bavarian counterparts, they weren’t too happy with unions, a staple of the German labor market. (“Bentonville … thought we were communists,” Poschmann, the union secretary, told the Times.)

Like so many other daily practices, in other words, the American smile is a product of our culture. And it can be similarly difficult to export.

Alice Roth contributed reporting